Thousands of weight loss drug ads found on Instagram

Online pharmacies, medical spas and diet clinics are running thousands of weight-loss ads on social media for the drugs Ozempic and Wegovy or for their active ingredient, capitalizing on a surge of interest in the medications but also angering some consumers who say they’re being inundated with ads suggesting they could benefit from the drug.

On Facebook and Instagram alone, there were more than 4,000 active ad campaigns in the United States mentioning semaglutide, the drugs’ active ingredient, according to multiple searches over several days on the ad library of the apps’ parent company, Meta.

By that measure, semaglutide is more heavily marketed on social media than even the erectile-dysfunction drug Viagra, which was mentioned in 800 active ad campaigns on Instagram and 930 campaigns on Facebook as of Monday and has long been known to be a favorite subject of online marketers. Meta does not provide spending amounts for such ad campaigns.

And it’s not just social media. Some consumers are complaining about seeing ads for weight-loss injections everywhere they look: on television, at signs near public transit, on the walls of airports and pretty much every other surface devoted to marketing.

The flood of ads indicates a rush by companies to capture new weight-loss customers after months of hype around Ozempic, a drug used to treat diabetic adults. With the help of celebrities and billionaires, versions of the drug have soared in demand this year as a temporary treatment for obesity.

On Wednesday, after NBC News sent questions about the volume of ads to Meta, the number of ad campaigns on its platforms dropped sharply to about 560 — a decline of 88% from a day earlier. A spokesperson for Meta attributed the drop to the company’s enforcement efforts. The company has a policy requiring advertisers to get written permission and provide evidence of an appropriate license before they can promote prescription drugs, and only online pharmacies, telehealth providers and drugmakers are eligible.

Facebook’s parent company has a long history of failing to catch ads that violate its rules — including for guns and opioids — and then removing them after journalists, watchdogs or everyday users find and report them. The review system is largely automated with software, according to the company.

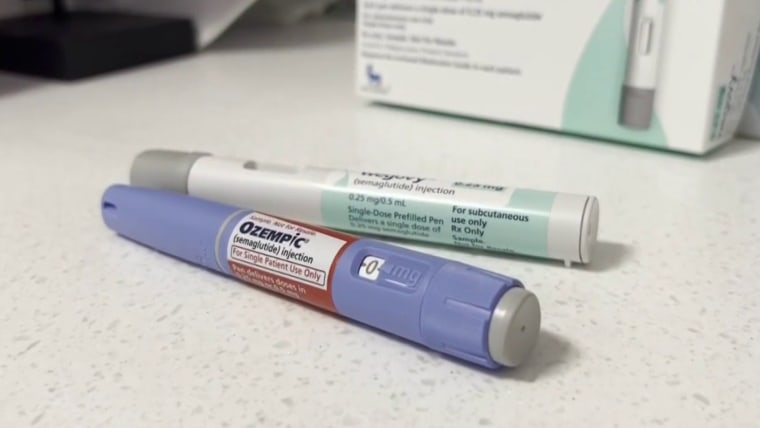

Ozempic injections are a prescription treatment to improve blood sugar in diabetic adults. There’s also a tablet version sold under the brand name Rybelsus. In 2021, the Food and Drug Administration approved a higher-dose version of Ozempic, called Wegovy, as a treatment for obesity in people aged 12 or older and for adults who are overweight with a weight-related health condition.

All three brand-name drugs are made by Novo Nordisk, a Danish pharmaceutical company. There are no approved generic versions of semaglutide, according to the FDA.

In May, Novo Nordisk said it was pausing its ads, citing a shortage of semaglutide and a desire not to stimulate further demand. Meta’s ad library listed 49 active ad campaigns by Novo Nordisk for Wegovy as of Tuesday. In a statement Wednesday, Novo Nordisk said it is still pausing all local television ads and postponing planned national TV ads for Wegovy.

But most of the ads on social media haven’t come from the drugmaker. Instead, the ad campaigns have been run by online pharmacies and lesser known marketers.

The surge in ads comes about two years after increased scrutiny of Instagram over whether the platform has contributed to body image issues and eating disorders among young women. Internal researchers at Instagram knew for years that the app was harmful to young users, especially teen girls, The Wall Street Journal reported in 2021. Since then, Meta has restricted how advertisers can target teens.

Jake Pikula, 28, said he first started noticing Ozempic ads on Instagram in late May and has gotten them several times a day since.

“I’ve never noticed a topic so much,” he said, adding that he was amused that Instagram’s complex ad system had chosen him as a target. “I’ve always been a little larger, so I laughed, ‘Oh, maybe I need it!” he said.

Pikula said he didn’t know why Instagram’s ad system had targeted him. There could be a wide array of reasons — Meta allows advertisers to target users interested in fitness or certain diets, for example — but Meta’s ad library doesn’t allow people to see how advertisers are targeting users.

Others have been more bothered by the ads.

Aly, a woman in Colorado Springs, Colorado, who asked to be identified by her first name only because she was speaking about a family member’s medical condition, said she was taken aback this month when Instagram and its video tab, known as Reels, served up an advertisement for Ozempic.

She said she began to pay more attention to cultural expectations around body image after a family member was hospitalized with the eating disorder anorexia. She even curated her social media feeds to cut out negative posts.

“I follow a lot of body positive accounts and people that are advocates for the plus-sized community,” she said.

So when the ad appeared in her feed, she was shocked.

“Why would I be the target audience?” she asked. “When that popped up I honestly thought it was a joke or a skit, but then I looked and it said it was sponsored. It said it could be prescribed online and it would be just so easy.”

Hadrian Flyte, a 34-year-old in northwest Arkansas, said his Facebook feed is choked with Ozempic ads — especially after he’s been at the gym or posted on Facebook about working out.

“It was rage-inducing, because I don’t need this thing and I don’t want these ads,” he said. “It seemed like it was trying to sell me a miracle drug.”

He said that, prior to seeing the ads, he had spoken with a doctor about taking the drug out of concern that he might become pre-diabetic in the future but had decided instead to focus on changing his diet and exercise routine. He said he finds the Ozempic phenomenon objectionable.

“I don’t think health care should be correlated with trying to sell a new thing,” he said.

The treatment isn’t without a downside. Some patients have reported side effects including vomiting and fatigue, and others say their weight bounced back when they ceased the weekly doses. Novo Nordisk lists several common side effects of Wegovy, including nausea and fatigue, as well as the more serious possible side effects such as pancreatitis.

Still, the demand for semaglutide drugs rose so much last year that there wasn’t enough to meet the demand for the drug’s other purpose: helping people with diabetes keep blood sugar levels in check.

The sharp rise in demand has also created an incentive for pharmacies to make or dispense unauthorized copycat versions of the drugs, prompting several states to threaten legal action against the pharmacies, NBC News reported last month.

Allison Schneider, a spokesperson for Novo Nordisk, reiterated the company’s position that it is taking action against these pharmacies, known as compounding pharmacies. It’s not clear how many of them were advertisers with Meta.

One advertiser, the health app and online pharmacy Ro, reversed course this week, saying it would pull back on advertising, including pausing all TV ads. CEO Zachariah Reitano said in a statement Monday on Ro’s website that he didn’t want to run ads when there already wasn’t enough supply of the drug to meet demand.

A second advertiser, NextMed, pulled its ads from Instagram and elsewhere in March, according to The Wall Street Journal, after the paper asked the company about ads that used before-and-after photos showing substantial weight loss by people who weren’t its clients. NextMed did not immediately respond to a request for comment from NBC News this week.

But even after those exits, Ozempic ads have still been coming in waves. As of Tuesday the number of ad campaigns mentioning semaglutide, the active ingredient in Ozempic, tallied 4,500 across Facebook, Instagram and other ad platforms operated by Meta, according to the ad library.

Meta declined to make anyone available for an interview about its policies and enforcement. A spokesperson said in an email that if the company finds ads violating its policies, it works to quickly remove them.

A smaller number of ads seem to be on TikTok. A search of TikTok’s ad explorer tool returned 394 ads for semaglutide in the past 30 days. TikTok says on its website, though, that advertisers must opt in to be displayed and that the tool may not reflect all ads.

Google, the biggest online advertising company by revenue, has its own ad search tool, but it allows people to search only by advertiser name or website, not by product or keyword. Twitter eliminated its ad transparency center in 2021.

Some consumers told NBC News that they had gotten Ro’s ads frequently on social media. As of last week, Ro was running 66 different ads on Instagram and Facebook, with about half of them, 32, devoted to Ozempic or Wegovy, according to Meta’s ad library.

More on Ozempic from NBC News

Ro, which has an emphasis on weight loss, sexual health, skin care and hair care, has faced questions about its marketing strategy before. In March, the company was criticized for running a weight loss ad campaign in the New York City subway system.

In a statement, the company said, “Our new marketing campaign, supported by clinical research and conversations with our patients, aims to start an important, sometimes difficult, conversation focused on de-stigmatizing obesity as a condition and highlighting a new, incredibly effective treatment that may, for the first time, be a real solution for millions of people.”

The statement continued: “We recognize that these are difficult conversations to have — and that not everyone will love our marketing.”

On Friday, a Ro spokesperson said that thinking applies equally to recent ads on social media.

The ads have become a flashpoint on social media. Sophie Turner, the actor perhaps best known for her role on “Game of Thrones,” complained in April in an Instagram post about the Ro ads appearing in the Times Square subway station. And TikTok influencers have slammed the ads, saying they imply that everyone should be 20% smaller.

Comedian Amy Schumer said that after trying the drug last year, she felt so sick she couldn’t play with her son.

But there’s a lot of money at stake, with the global obesity therapeutic market set to be worth $200 billion within the next decade, analysts at Barclays said in a research note in April.

When Ian Kar, a 31-year-old venture capital investor in Los Angeles, started to see ads for Ozempic on Instagram, he interpreted what he saw as a classic Silicon Valley tech startup move: use social media ads to drive fast sales growth at nearly any cost.

“A lot of startups, given the market, they’re trying to figure out new ways to grow,” Kar said.

In this case, though, he said he thinks tech startups are going too far, especially given how many young people on Instagram are dealing with eating disorders or working through questions about body image.

“It doesn’t teach great behaviors,” Kar said of the ads. “It teaches people that there’s a magic pill out there for weight loss.”

In addition to its rule restricting who can promote prescription drugs, Meta has guidelines for advertisers to follow including for health-related ads, including a ban on health ads that imply “unrealistic or unexpected results.”

The FDA regulates how prescription drugs are promoted, including on social media, and its website has contact information for reporting potentially false or misleading ads.

Erin Willis, an associate professor of advertising, public relations and media design at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said drugmakers and other marketers are increasingly turning to social media including paid influencers in order to boost sales. She published a paper last year in the Journal of Medical Internet Research documenting the influencer partnerships.

“This is one way for pharmaceutical companies to cut the clutter and get their message directly to consumers,” Willis said.

The volume of advertising is alarming for some patient advocates who are concerned that the marketing amounts to hype and doesn’t include sufficient warning about the risks of the injections.

Sneha Dave, executive director of Generation Patient, an advocacy group for young adult patients, said federal regulations that govern drug promotion haven’t kept up with changes in social media such as the growth of short-form video on Instagram and TikTok.

Until regulators issue more guidance, she said, consumers should be extra vigilant about researching risks.

“They can seem all great for how well they work, but there are always safety concerns to be worried about because at the end of the day, these are serious chemical compounds,” Dave said.