National Latino museum’s funding threatened by congressional clash

A funding dispute between lawmakers who’ve been working for decades in a bipartisan effort to create a national Latino museum underscores the challenges around defining U.S. Latino history amid increasingly partisan culture wars.

Republicans who pushed to defund the Smithsonian’s upcoming National Museum of the American Latino and the Molina Family Latino Gallery — a small space inside the National Museum of American History used for temporary exhibits featuring Latino history— may be having a change of heart after seemingly reaching some common ground with Smithsonian leadership this week.

Rep. Mario Díaz-Balart, R-Fla., and Rep. Tony Gonzales, R-Texas, co-chairs of the Congressional Hispanic Conference, led a meeting Tuesday with Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III and his staff after feeling “deeply disappointed and offended” by a bilingual exhibit titled “¡Presente! A Latino History of the United States,” they said in a joint statement Wednesday evening.

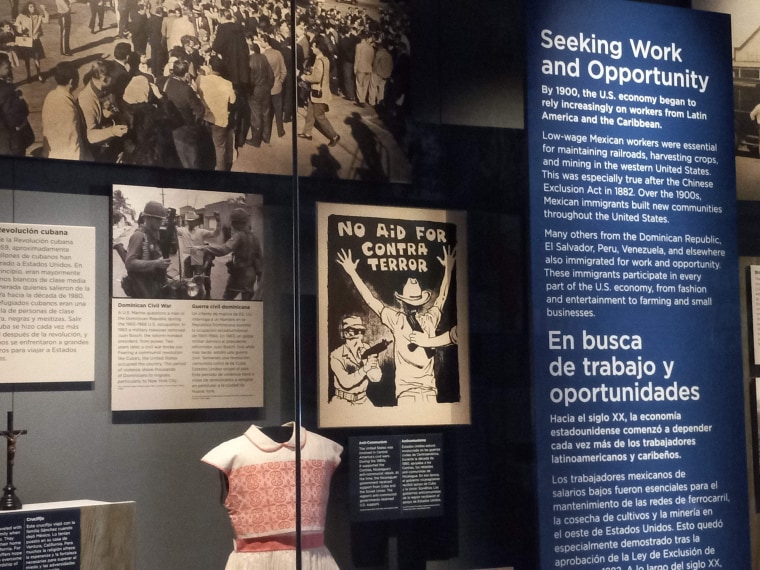

The exhibit in question was promoted as “a preview” of the national Latino museum’s potential when it opened last year at the Molina Family Latino Gallery.

But shortly after its debut, conservative Latinos criticized the exhibit for elevating leftist ideologues, celebrating LGBTQ Latinos and advancing “the classic oppressor-oppressed agenda,” among other concerns. They called for the national Latino museum’s defunding.

These concerns reached the House Appropriations Committee this month. In a mostly party-line vote, the committee approved a Republican bill that included zeroing out federal funding for the “planning, design, or construction” of the national Latino museum and the operation of the Molina Family Latino Gallery.

“Defunding the museum now may mean that it may be delayed 10 more years,” Rep. Rosa DeLauro, D-Conn., said during a committee hearing last week.

But after Tuesday’s meeting, Díaz-Balart and Gonzales said the Smithsonian showed serious commitment to rectifying its actions. “Procedural changes in the review of content and leadership have been made,” effectively opening the door “to allow funding to go further,” they said in a statement.

The current Molina gallery exhibit features significant figures such as Indigenous freedom fighter Toypurina, Mexican American civil rights leader César Chávez, Puerto Rican baseball star Roberto Clemente, Guatemalan labor organizer Luisa Moreno, Colombian American drag queen José Sarria and Cuban American singer Celia Cruz, according to the Smithsonian.

The 4,500-square-foot gallery showcases historical artifacts, documents and personal stories. The elements are organized under four historical themes: “Colonial Legacies,” “War and U.S. Expansion,” “Immigration Stories” and “Shaping the Nation.”

According to the Smithsonian, curators have said the “¡Presente!” exhibit was developed based on conversations that curators had with museum visitors about what they don’t know about Latino history.

Whose history?

When Congress approved legislation in 2020 to start the process of creating a national Latino museum, some federal funding was appropriated to the Smithsonian to get the ball rolling.

That legislation included language agreeing not to portray a single political ideology in the museum’s exhibits.

Rep. Mike Simpson, R-Idaho, the current bill’s main sponsor, said he included the defunding language in support of his Republican Hispanic colleagues who expressed “serious concerns” about Smithsonian exhibits promoting socialism and depicting Latinos as victims. They pointed to some examples.

According to Republican committee members, the creators of the exhibit chose to highlight a convicted military deserter instead of “the thousands of courageous Latino military heroes that served our country proudly and honorably.”

After Díaz-Balart voiced some of these concerns during last week’s hearing, Rep. Adriano Espaillat, D-N.Y., defended the exhibit, saying that “dissent is patriotic, it’s at the very core of democracy … To disagree when something is wrong, to right a wrong, is more American perhaps as much as the Constitution of this nation.”

Espaillat added that he can agree with some of the concerns, but “there are dozens, maybe hundreds, of parts to that exhibit” reflecting a wide range of Latino experiences from people with similar heritage, but distinct identities.

“And just because we cannot agree, we disagree on one part of it, we’re going to drive a stake through the heart of what could be a major institution for the Latino community? I think that’s flawed and mistaken,” said Espaillat, who’s also deputy chair of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus.

Another example cited by Republicans was “the lightness with which serious topics are portrayed, such as scented exhibits meant to simulate raft rides of those risking their lives to flee tyranny, romanticization of socialism, and failure to adequately document or portray the reality of totalitarianism.”

During last week’s committee hearing, Díaz-Balart said he first expressed these concerns to the Smithsonian back in December, but the institution responded with “lip service.” Republicans argued the only way to make the Smithsonian act on their concerns was to withhold funding.

A spokesperson for the Smithsonian told NBC News they don’t comment on pending congressional legislation including appropriations.

Even though the fight over the museum’s funding has moved outside the committee’s reach following last week’s vote — making it harder for lawmakers to reverse course — Díaz-Balart and Gonzales said they’re engaging in discussions with Simpson and other members to provide federal funding for the national Latino museum following their meeting with the Smithsonian.

What’s next?

As of Thursday, it’s unclear how much more lawmakers do to change the provision defunding the museum before Congress leaves for recess this weekend.

The museum’s funding dispute comes as the House gets ready to vote on a series of spending bills for fiscal year 2024. While the bills are part of a routine appropriations process to fund government agencies starting in October, Republican policy riders have included language on some of these must-pass bills targeting critical race theory, diversity efforts, drag shows and Pride flag displays.

The national Latino museum is expected to cost between $600 million and $800 million; half of the funding will come from Congress and the other half from private fundraising. That fundraising process could greatly benefit from having a permanent home for the museum selected, museum supporters have said.

Two sites by the National Mall are being considered. Both sites are property of the National Park Service; ownership would need to be transferred to the Smithsonian before any construction could begin, and the construction has to be approved by Congress. By law, a site for the museum has to be designated by Dec. 27, 2024.

It took the Smithsonian 10 to 15 years to create similar museums such as the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the National Museum of American History.

For the first time in its history, the Smithsonian is simultaneously creating two museums from scratch, the National Museum of the American Latino and the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum. Unlike the Latino museum, the women’s museum hasn’t endured any defunding or delays, according to the Smithsonian.